This piece is informed by reproductive justice-led work in Appalachia during Hurricane Helene recovery, where community care networks step in as a matter of practice when systems fail.

For 53 years, the anniversary of Roe v. Wade has held a mirror to the sector. Too often, what it reflects back is the cost of our own silence, absence, and hesitation to invest in abortion access at a scale that the frontlines have long demanded beyond survival and beyond sustainability.

Since 2020, the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy has worked to move research, resources, and guidance toward abortion access rooted in justice, centered at the state, and local levels, and shaped by those closest to the hurt and work. And still, nearly four years after the Dobbs decision, the limits of research alone have become undeniable. Philanthropy continues to underfund, delay, and constrain the movement’s vision, while anti-abortion forces do the opposite. Anti-abortion funders build patiently, plan across decades, and their funding does not excuse itself during legislative fads and ballot calendars.

Meanwhile, much of abortion access-centered philanthropy remains preoccupied with its own sunsets. Convening to discuss exits, legacy, and the vacuums their absence will create, rather than reckoning with the damage already done by years of underinvestment, silence and stigma. As of this anniversary, several major institutions have publicly announced plans to wind down or exit the field, including the Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation, the movement’s largest funder, the Compton Foundation, the Gates Foundation, the Grove Foundation, the Irving Harris Foundation, the Wellspring Philanthropic Fund, and the Tara Health Foundation.

Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation’s decision to sunset has surfaced a reckoning the sector postponed for far too long. Its scale and steadiness created tangible stability and in doing so, made it easier for the rest of philanthropy to avoid building shared responsibility, redundancy, and long-term infrastructure. The panic we are witnessing now isn’t about one foundation stepping back; it’s about a system that never prepared itself to hold the work collectively.

As others wait to make their plans public, philanthropy infrastructure organizations like Funders for Reproductive Equity and intermediaries like Groundswell Fund and Grantmakers for Girls of Color continue to fund grassroots work while also challenging the habits philanthropy has relied on for too long. Those reckonings matter. Because at this moment, abortion seekers, providers, and organizers are exhausted. Their grace is gone, and their patience is low.

And exhaustion on the frontlines is not just an emotional condition; it is the terrain on which opposition infrastructure is built. Appalachia shows us exactly how that transfer of power happens.

Maternal Health Deserts and Manufactured Scarcity

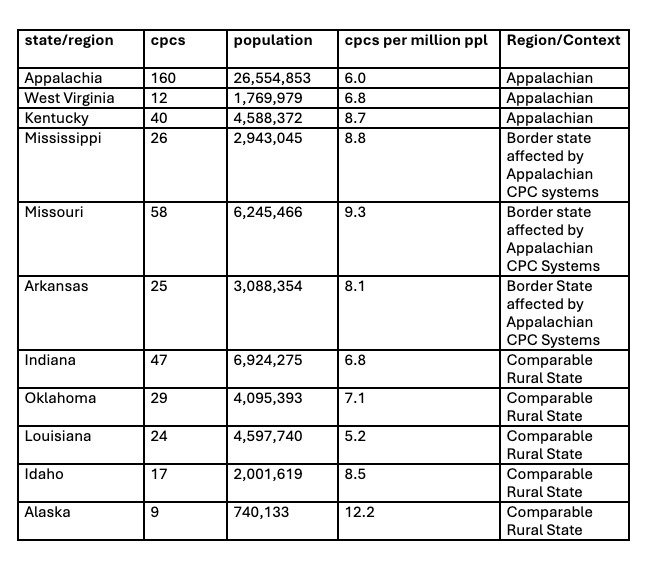

We are naming Appalachia not because it is marginal, but because it is revealing the impacts of a sector that has produced and sustained isolation in a region considered nonessential to national strategy. The expansion of crisis pregnancy centers (CPCs) in the region is not simply the result of opposition strategy; it is the predictable outcome of philanthropic absence. When long-term, values-aligned investment fails to materialize, anti-abortion infrastructure fills the vacuum with discipline and